Interview: Christie Draper

Interview: Christie Draper

by Grace Lilly

How did Dylan come out to you?

Dylan came out to us when he was 15, but he’d been out to his friends for about a year before that. Unfortunately, that was the year of the Prop 8 situation and at the time we were going to a very conservative, fundamentalist church. Of course, they were taking a political stand from the pulpit, saying: “The world is going to come to an end if Prop 8 doesn’t pass”. So, being the good sheep that we were, we voted yes on Prop 8, and I’m sure those conversations contributed to him not coming out to us earlier.

We started suspecting he might be gay. One time, at about three in the morning, he came in and I woke up and his little face was right next to the bed. He was looking at me right in the face and said, “Mom, I need you to come to my room; I need to tell you something.” So I went into his room and it took him probably 45 minutes. He just sat down on the bed, legs folded, and put his head in his lap and just cried and cried and cried.

Finally I said, “Dylan, are you trying to tell me that you’re gay?” And he just nodded his head. He laid back on the bed and you could just see this relief. Just like his whole body relaxed like, “I did it. It’s over with. It’s all over.”

So for the next probably two hours, I stayed with him and we just talked. And I asked him all the stupid questions, “Dylan, do you think you’re always going to be gay? Did you never like girls? Do you think you’ll ever be attracted to girls?” All the things that you ask as a parent who is ignorant—all the questions that since then I’ve heard other parents asking their children as well. And of course those questions seem utterly ridiculous to us now.

What was your biggest concern when he told you?

Tremendous fear. There was this horrible fear that he was going to be killed, or that he would get beat up, or that people were going to bully him for the rest of his life, or that he would get AIDS. I think the overwhelming feeling was fear for his safety.

So would you say your family had a turning point when he came out in terms of your views on gays and lesbians?

Oh, absolutely. The interesting thing is, I grew up in a medical family—my mother is a nurse and my father was a doctor. Neither of them ever thought that being gay was a sin, and neither of them felt that being gay was a choice. And the interesting thing is that I didn’t either. I didn’t believe being gay or being in a gay relationship was a sin. And I didn’t believe that it was a choice. The issue for me was around the marriage debate: should gays and lesbians be able to marry? Of course that was just a question of ignorance, because to say “This is my common-law” or “This is my partner,” versus “This is my husband” is very different, and I did not understand the real significance of the marriage debate at the time.

So after our son came out, we actually made an appointment to see a counselor at the church. We went to one of the mega-churches with thousands of people, and it’s a very fundamentalist, very profitable type of place. We sat down with one of the pastors and explained the situation. Then the pastor suggested that we send him to this program called New Horizons. It’s basically an ex-gay therapy program, which are now illegal in California. At that point I stood up and I just walked out. So that was the story of how we left our church.

So were you able to find support in other ways?

Interestingly enough, we went to Dylan’s pediatrician, who very matter-of-factly told us that Dylan should be checked for HIV every six months, and that we needed to find him a gay-friendly counselor. He said, “Even though he’s only 15, he’s had probably a good 10 years or so of internal struggle about this issue. And he is going to need to work through those things.” I found a counselor who had a son, who was 23 at the time, who was gay. She took us immediately, and told us to go home and look up information on PFLAG. The next time we came in, she had a whole folder of information for Dylan: a list of books, a bunch of information on PFLAG, that kind of thing. That next month we went to a PFLAG meeting and we have been going ever since. We have a saying in PFLAG that when you stop needing PFLAG, PFLAG starts needing you. So that’s why we’re still going. It was PFLAG connecting me with other parents that helped me most.

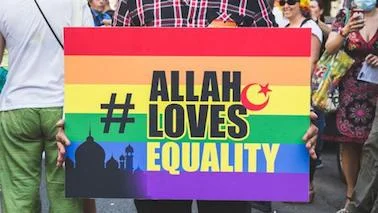

We did find some very gay-friendly churches and I actually spoke with some of the pastors who immediately told us, “I am so sorry that your family had to go through this, because it’s wrong. Dylan is exactly who he’s supposed to be.” That was really neat—seeing that not all churches and not all people of faith are homophobic or bigoted or discriminatory. And just hearing those words, “I’m so sorry” was really cleansing and healing. We’re still people of faith, but what I do mostly with people is focus on religious-based bigotry. Because I think that is the root problem in this country, and probably around the world. But in this country it’s definitely that the root is fundamentalist religion causing all the hatred and the violence and all these things against the LGBTQ community.

Could you speak a little bit more about that?

For every person I’ve ever spoken to who has an issue with LGBTQ people, their rationale is always religion. They say, “God is against it. I just believe what the Bible says.,” It’s all rooted in that fundamentalist, very hypocritical picking and choosing of Bible verses. I think that at least until the church comes around on this issue, like they did with interracial marriage, there will continue to be discrimination towards LGBTQ people. Because they can’t separate their “beliefs” from how they act. It’s one thing to say, “I don’t think God endorses LGBTQ relationships” and it’s another thing to go out there and vote against rights for LGBTQ people. Everybody has their personal biases and prejudices, but when they actually put action to it, that is when they become a bigot.

Do you feel differently now than you felt in those initial moments, or first few years?

I’d say I was initially focused only on Dylan and helping our son be safe and work through his issues. But apart from Dylan now, I’m an activist. I am never going to stop this fight until I die. Working as an outreach coordinator, I talk with people on the phone and online a lot and there’s so much suffering. When I talk to kids and I see what they’ve gone through with parents, and the rejection and the suicides. Dylan always says: “My mother is so much gayer than I am,” because he’s moved on to other things and obviously this has become my personal crusade.

I remember one night, I think it was my second time there, we were going around the circle and sitting next to me was this man, Todd. His husband was there and I spoke about Prop 8. My heart was beating really fast because there were a lot of gay people in the room when I said, “It’s really painful for us because we voted ‘yes’ on Prop 8.” I turned and looked at him and the look on his face was like he was in such pain. He looked at me and his comment was, “I’m so sorry.” It was like he could see the pain I was going through because I had basically voted against my own son. He wasn’t angry with me, he wasn’t bitter against me, he was just sad for me. And I think that was such a turning point for me—if he can forgive me, I should be able to forgive myself, move on, and do something about it.

I share this with the group a lot: there’s a lot of great things that have happened to me. I got married, I have three children, all amazing moments, but the best thing that has ever happened to me as a person, as a human being, was having a gay son. Because it’s literally changed me from the very core of my being. When you have children, it’s like wearing your heart on the outside of your body for the rest of your life. A lot of people who don’t have kids don’t understand that you literally would die for your kids because you just love them so much. When Dylan came out that this was such a part of him, it became a part of me and it became my personal battle. My agony, my pain, my hurt. So when I see other children, I feel that same pain. I am so grateful because I know I would not like the person I would have been had our son not come out. It’s made me a much more accepting, loving person than I ever would have been.

If you could do it all over again, is there anything you would change?

Yes, I would change everything from day one, from when we had our children. And I always tell people who have younger children, “Make your house a safe place for anybody because you don’t know and you can’t pick.” You don’t get to choose if you have a gay child or a transgender child or a bisexual child. And you may think that by taking them to church and pounding religion into them is going to prevent it from happening. But obviously it doesn’t.

If I could, I would go back to the very beginning and just make it a non-issue: talk about gay people and gay marriage as, “They have the same rights as everybody else or they should have the same rights as everybody else. They’re people too. God created them too.” It would’ve been a completely different take on not only gay people but everybody. “Thou shall not judge,” would’ve been the rule of the day in our house. Thou shall not judge by how they act, by how they are, by how they speak.

Want to become a volunteer writer? Tell us here!

Austen Hartke's new book shows the world that transgender Christians have always existed, and is an incredible resource to help Christian parents, leaders, and community members understand how trans folks experience Christianity.